In the middle of last year my co-teachers and I started looking at the possibility of implementing a personalisation model in our Primary Years learning area. There are a lot of positive reasons for us to do this, as we are a big learning area, with over 150 year 6/7 students in the one building. While this may sound like a disadvantage to some, the opposite has usually proven to be true. The opportunities for providing diverse, cross curricular programs, with multiple options and entry points for the wide ability ranges represented within the building, as well as the collaborative approach to planning provide us with the opportunities to try many innovative projects, and work together to share our discoveries as educators. The latest step is designed to address the difficulties surrounding the spread of ability over the Primary Years. (In some cohorts this ability range has spread from year 1 to year 10). Personalisation seems to be the best way of addressing this. Hopefully soon I will have written a post about our thinking and steps towards this process and when I do, I will put a link to it here… (NOTE: Until there is a link here, feel free to chide me endlessly in the comments until I write something. I need to be externally motivated sometimes.)

As described in previous blog posts, I had been inspired by Edutech presentations by Ian Jukes and Ewan Macintosh, as well as Sir Ken Robinson and Dan Haesler. I had experimented with ungooglable questions in the classroom in the latter half of 2014, and this process, while enlightening, had also thrown up some pretty big deficits in the class skill set. With the long term view of creating a personalised learning space across all five Primary years Classes, we quickly realised that these were a range of skills that all of our students would need if they were to be successful in a personalised environment.

Overwhelmingly, this new cohort of students (the new year six students at least) had also come from classes where much of the learning had been worked through together, where the focus was still mostly on personal individual capability and individual product. Taking risks and problem solving were not skills that they had even begun to develop.

As previously noted, the 21st century learning skills focus on Collaboration, Problem Solving and Critical Thinking. To make the most of these abilities, students also need to develop other skills such as time management, research capabilities and higher order thinking and questioning.

How do we teach that? The ideas of Ewan Mackintosh had been a great jumping off point in terms of higher order thinking and further research combined with some handy links from my line manager threw up the idea of design learning as a possible next direction. But the teaching of Higher Order thinking, while very, very important, wasn’t on it’s own going to cut it, especially at the start of the new year. Asking students to launch straight into unGoogleable questions and higher order questioning with no lead in was a big ask. So we rescheduled this for later in the year. Having trialled unGooglable questions in term three and four last year, it has become evident that before we can unpack higher order thinking, we need a solid basis in some other, more basic, skills to support us.

How do we teach that? The ideas of Ewan Mackintosh had been a great jumping off point in terms of higher order thinking and further research combined with some handy links from my line manager threw up the idea of design learning as a possible next direction. But the teaching of Higher Order thinking, while very, very important, wasn’t on it’s own going to cut it, especially at the start of the new year. Asking students to launch straight into unGoogleable questions and higher order questioning with no lead in was a big ask. So we rescheduled this for later in the year. Having trialled unGooglable questions in term three and four last year, it has become evident that before we can unpack higher order thinking, we need a solid basis in some other, more basic, skills to support us.

Our middle years learning space already works in a collaborative way. We run activity sessions once a week, where students book into their choice of session. We run a kitchen and garden program that allows all students to work in groups and create dishes and grow fresh vegetables. We run a robotics program and trialled a TV studio. These options are accessible to all students, with each teacher designing the lessons. In 2014 we also trialled a Natural Maths program, running concurrently with three classes. Students work collaboratively across the learning space with extra support from SSO staff. (We have since expanded this model to all five classes.) It is fair to say that when combined with team planning, and shared resource development, we work well as a collaborative team.

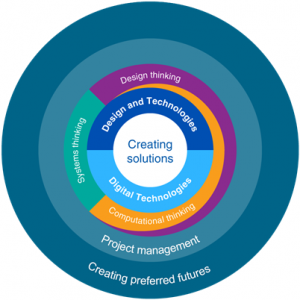

So when I looked at Design Learning, I could see that we could become more explicit about the skills needed to realise the 21st century skillsets, whilst also covering the new Digital Technologies Curriculum processes and production skills, science content (particularly water & electricity) and elements of HASS.

The process and production skills in the digital technologies curriculum include Defining, Designing, Implementing, Evaluating, Collaborating and Managing. These are broadly similar skills to those advocated in the design learning process I had been researching.

The process and production skills in the digital technologies curriculum include Defining, Designing, Implementing, Evaluating, Collaborating and Managing. These are broadly similar skills to those advocated in the design learning process I had been researching.

Design learning also suits the needs and talents of the more ‘hands on’ and ‘verbal’ learners in our learning area. These traditionally overlooked and usually unsettled cohort of learners have an opportunity to model their skills to the more traditionally successful ‘sit and listen’ students. These students had been very successful in the kitchen and garden programs, and right from the beginning of the design process, different faces have came to the fore to lead their teams.

So design learning looked like the stepping-stone we needed between collaboration and personalisation. I set about trying to create a design learning program that would teach students how to work collaboratively, to solve problems, research their solutions and present their findings clearly and critically to the group.

So as far as broad ideas went, I was brimming with choices. There were a wide range of differing approaches to be found, with slightly differing terminology and process steps to be found all over the internet. Some of the processes focussed on the ‘making and design’, some on thinking and research. There was, however, nothing that fit the cohort’s needs as a ready-made process. The question was, where to start.

I read as much material as I could from a range of websites. Macintosh and Sugata provided some great ideas with their processes.

Corporate websites that advocated design-thinking processes were also a valuable source of information and there were many links to University You Tubes and education specific models such as this very helpful one that eventually formed the basis for our program.

From this base of reading I started to better understand the process, and started to cobble together a plan. This understanding phase is critical, in that it frames the needs of the process, and sets the goal and success criteria for all that follows. It also gave me enough of an idea of the differing ways of using design process that I felt much more confident in adapting what I found instead of just using it.

Next, I created a draft process that I could use in my own class, to trial the process and to see what I could learn. My class this year is one of a lower literacy and research skill level, and so I designed initially a process and a program that involved solving a problem in the school garden, namely, keeping it alive over summer. It involved group activities, brainstorming, and design research. The overall scaffolding worked pretty well, but the researching and mind mapping skills were too advanced for the class and I had made many, many assumptions about the capabilities of the group. Not all of these sessions met with success, but there were many elements that worked well, elements that underpinned the ideas of working collaboratively and sharing what we discovered. I surveyed the class to get some feedback on this, and started to make adjustments for the new year.

So I played a bit of pick and choose between those elements that worked and those that needed to change. Between those that needed more scaffolding to improve the success rate of students and those that worked well from the outset. I created a process and explanation of the steps as I envisioned them coming about and proposed a series of test lessons that we could use in the first part of this year in order to share the process with colleagues, and to refine what I had learned so far. I chose the most effective elements and removed or significantly altered many others. I started to create a program that could be easily picked up by colleagues and run with.

The second run through the process was set for term one this year. There were already many changes in this modified run, not the least being the goal: in this run through, the end result had a focus on creating a physical model of the solution to the problem at hand, rather than a real world solution to be hopefully implemented within the school. Although it is pretty clear from research (link) that real world problems are great motivators, at this point the chance of the school going ahead with a real life garden redesign were slim. The kids knew this and so there was a sense of ‘what’s the point?’ Students were clear in their feedback that in the end, if we weren’t going to actually build the garden solution, we were wasting their time. My attempts at selling this first garden problem as a thought experiment rightly fell on deaf ears. In the second round, the financial restraints are still the same, but by making the end product a plan and model that can be proposed to the principal, the students have a concrete goal that won’t kill the budget. There is a more tangible end product, and this seems to suit the process better than an abstract outcome. In the next round, a real world outcome of manageable proportions will be the goal. As a side benefit, the model making elements of this task help meet the criterion of design and technology in the digital design curriculum. As a downside, this area needed a lot more scaffolding and materials, both for students, and for myself.

The second major change was that I knew that I would be sharing the results of this current run through with my colleagues. I was keen for them to take a few lessons themselves and introduce the lab to their own classes. I had created a pretty serviceable framework and working space, but the biggest stumbling block so far had been that much of the process was still stuck exclusively in my head. I had also noticed some potential trouble spots, and some areas where, although I knew what I was doing, I knew I would need more detail and resources created in order to hand over to other teachers and have them be successful.

So I started researching again. I looked for specific lessons to support the skills of each lesson, to plug the gaps and assumptions I had made about my students and the lesson steps. It was at this point that I found the going slowest, and noticed that I was second guessing all the ideas I’d used, and wondering if I had misinterpreted, if I was ‘doing it wrong’.

The solution was obvious: use the process itself. I realised at some point that I was essentially trying to create a ‘finished product’ for my

colleagues. The Irony of doing this for a design learning process was not lost on me. So instead of presenting to colleagues a finished product, I decided to get them into the lab and run through with them how the process works right now. And within fifteen minutes of walking into the lab they were questioning, suggesting and working on modifying it too. It’s early days, but one single session of sitting in the space and discussing the process with colleagues has already thrown up some excellent changes.

Like I say: Obvious.

When I was working on my own, the pace was glacial. I second-guessed and dithered a lot. As soon as I reviewed the first run with students, decisions started to happen. When I brought in my colleagues, things changed even more quickly. After that one meeting I’m already looking at changes for the next process and most importantly, so are they.

It’s moving quicker, and it is happening with more confidence now because I’ve got more brains working on the problem. That’s why more brains are better than one…

We’re using design thinking to think about designing effective design thinking.

And so now I get to put this all into practice. I’ve created rubrics and mini lessons and curated useful links and videos and more. I’ve got my colleagues on board to start their first design lessons in the next week or so. They will provide me with a lot of feedback, because they are that kind of people and I will go away and make changes. They will go away and make changes. Then we will run it all again. And then we will make more changes.

We will keep the original brief in mind: To develop the skills of our students in Collaboration, Critical Thinking and Problem solving so that later down the track when we personalise their learning space, they have the 21st century skills they need to make it in that space. Because if we can do that in here, they can take those skills out into the real world and endlessly adapt them to whatever is put in front of them.